Processing PubChem with Polars (Python)

How to wrangle the world's largest chemical database on your laptop.

Wrangling ~100 million molecules with ~100 lines of code in ~10 minutes

PubChem is the world’s largest publicly accessible database of chemical information, aggregating data on over 100 million molecules with cross-references to over 1000 data sources. Its excellent user interface and versatile API provide pretty much all of the information a chemically-minded scientist would need about a given molecule.

But what if having a lot of information about a given molecule isn’t enough? What if we need all of the information about all of the molecules - for example, to train a machine learning model, or to assemble a reference database for untargeted analytical chemistry? In these cases, the usage policy’s limit of 5 API calls per second will not suffice.

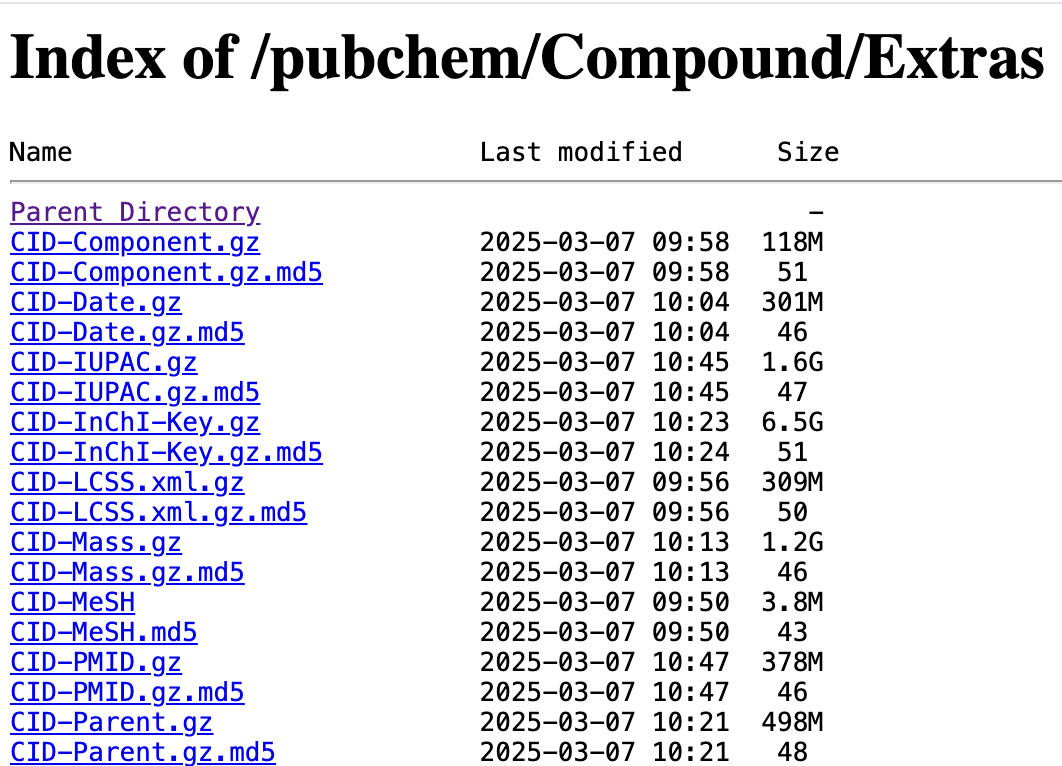

Fortunately, PubChem offers generous bulk downloads that are updated daily. So for example, if we wanted to generate a table comprising millions of chemical structures, along with their names, molecular formula, and any cross-references to biological databases (e.g. HMDB, KEGG, ChEBI), we can do that by extracting and transforming the records contained in PubChem’s compressed, tab-delimited files1.

These files are pretty big, yielding dataframes that would require more RAM than is available on most consumer hardware. Fortunately, we can take advantage of polars with its excellent Lazyframes to process datasets that don’t fit into memory.

We’ll start with some definitions, then describe the workflow, and finally wrap up with a conclusion.

Definitions

Before we get into the actual code, we’ll define our inputs and output.

Inputs

First, some chemi-informatics:

Molecular Formula - the number of each element comprising a molecule, e.g.

C5H10N2O3SMILES - a compact string representation of the structure - may include localized charges and chiral centers, e.g.

C(CC(=O)N)[C@@H](C(=O)O)N

Second, the major biological compound databases we will cross-reference2:

ChEBI - Chemical Entities of Biological Interest, e.g. CHEBI:28300

HMDB - Human Metabolome Databasem e.g. HMDB0000641

Finally, some PubChem specific terminology:

Title - the common or preferred name for a given compound e.g. Glutamine, as opposed to its UIPAC name, e.g. (2S)-2,5-diamino-5-oxopentanoic acid

CID - Compound Identifier, e.g. 5961

SID - Substance Identifier, e.g. 175265821

PubChem Compounds, indexed by CID can be thought of as curated, abstract representations of PubChem Substances (indexed by SID). Fortunately, all of the tables we will be merging contain a CID column, so we won’t need to perform complicated multi-table joins.

Ouput

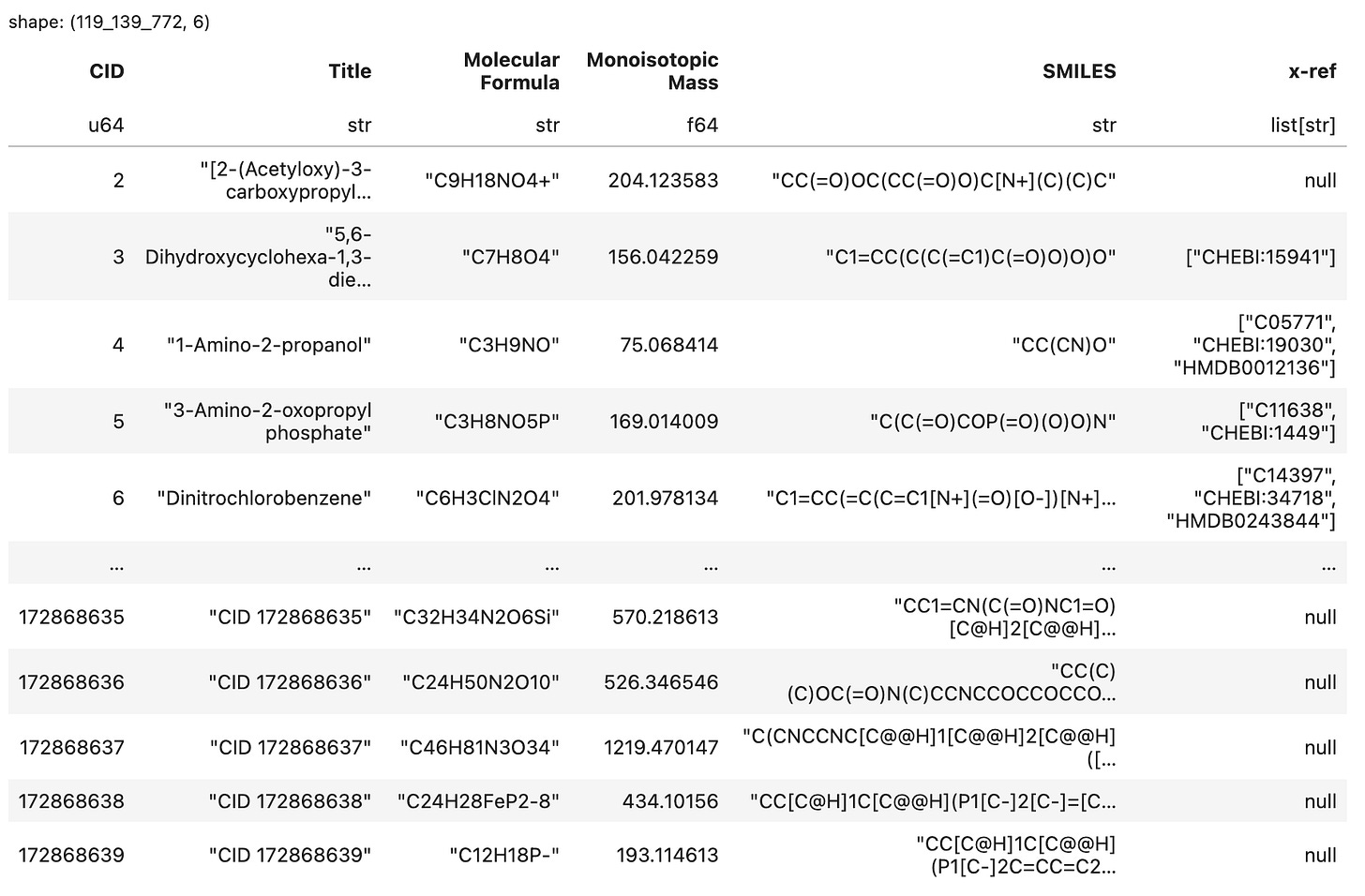

This is the table we will generate, saved to .parquet format3.

Workflow

Note: Because Substack’s code blocks are pretty clunky, I’m going to rely on screenshots for most of this section and collect the Python code blocks in an appendix.

1. Set up the Python environment & open a new Jupyter notebook

We’re going to use uv to boot up a Jupyter Lab instance with polars and requests as the only dependencies4. Make sure you have uv installed (any version above 0.6 is fine), then run the following shell commands:

mkdir pubchem_polars

cd pubchem_polars

uv init --bare --no-readme

uv add jupyterlab polars requests

uv run jupyter lab2. Define loading functions

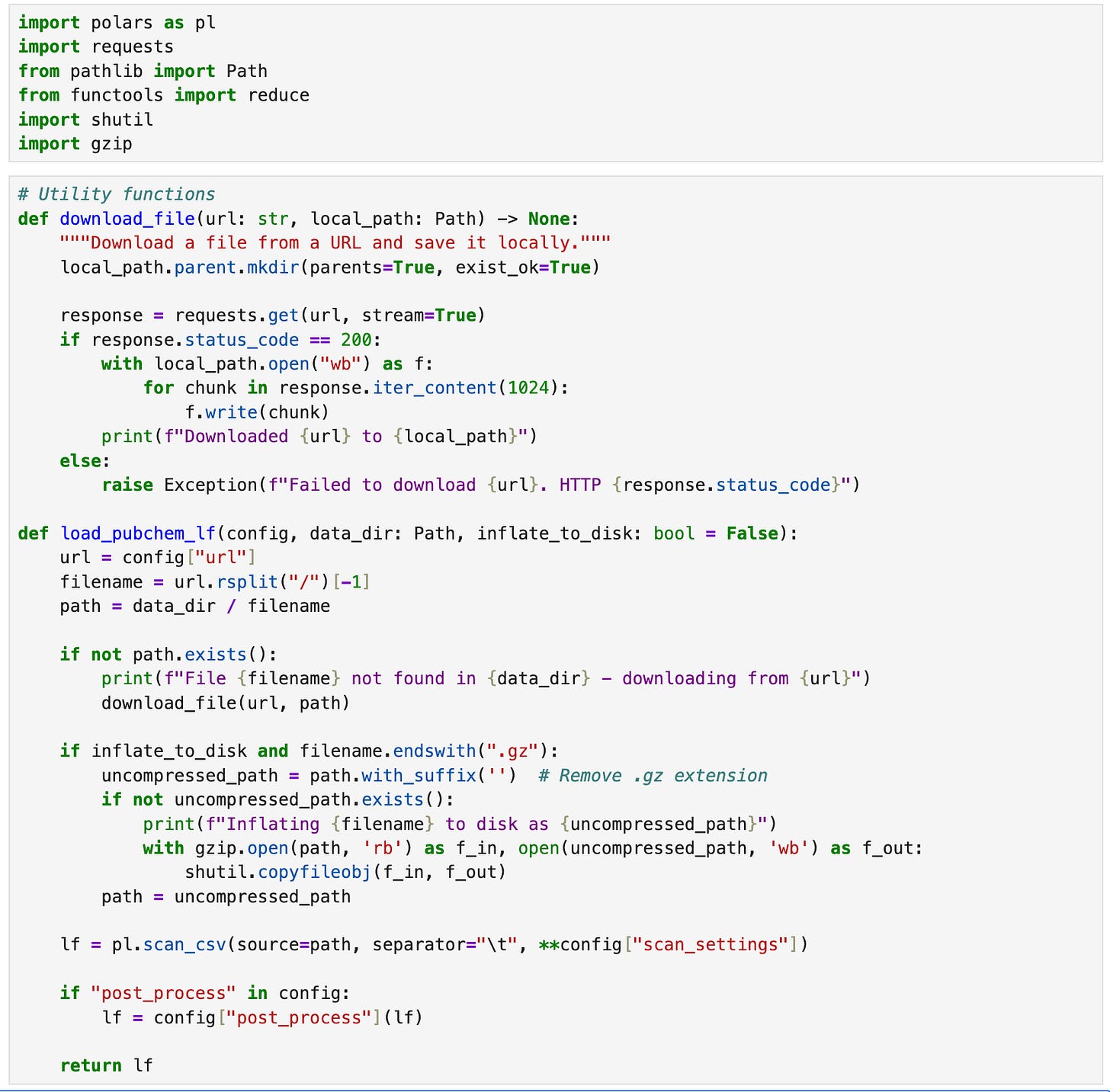

While polars can load - and even stream - data from remote URLs, we’re going to download a local copy of the PubChem files we need to ensure that we only download and decompress the data once using a helper function load_pubchem_lf.

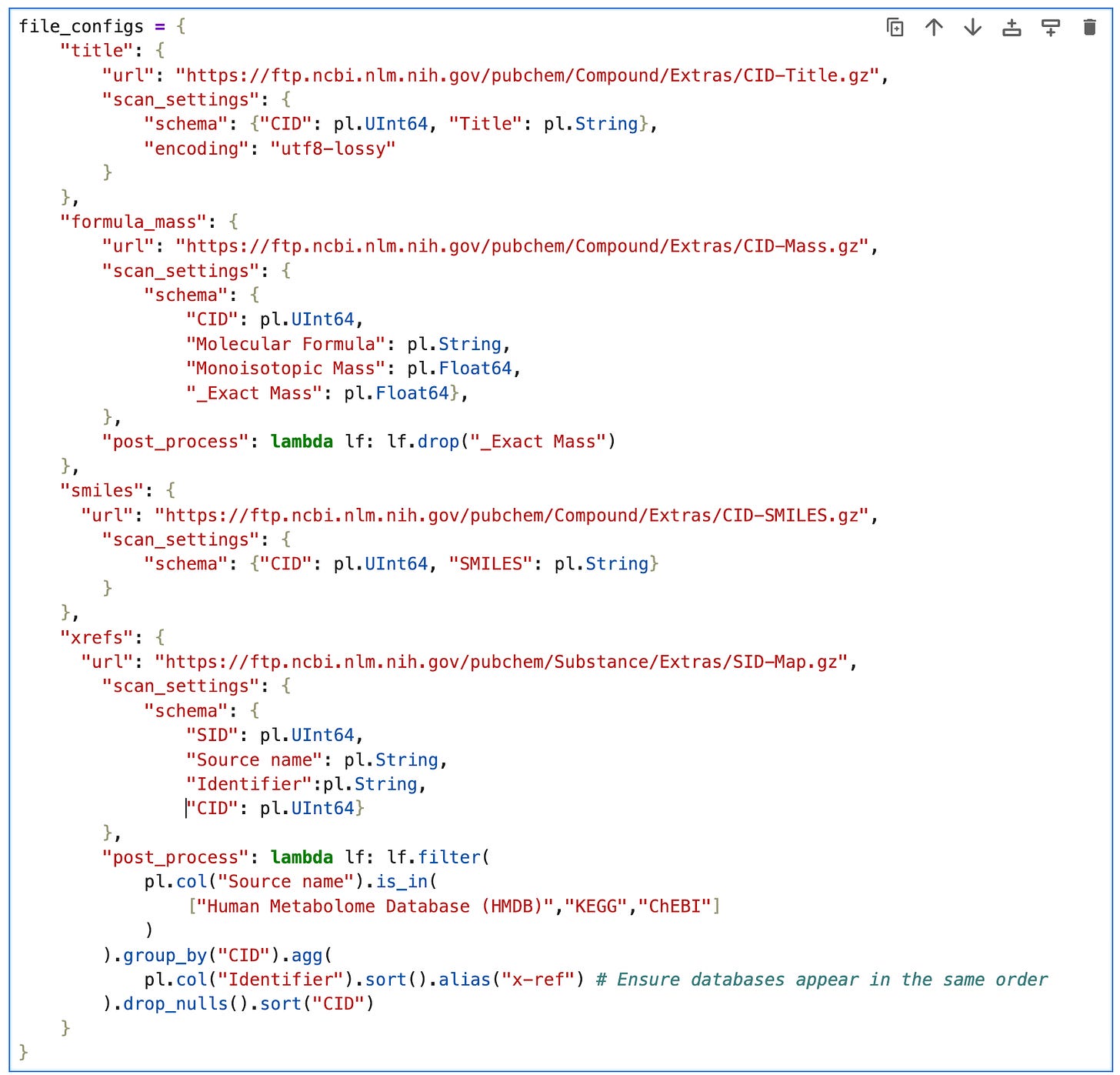

3. Define loading configurations

To avoid repetition, we’re going to create a dictionary file_config containing everything we need to configure to load the data, i.e.:

url: the remote data source on the PubChem FTP serverscan_settingsschema: a dictionary of column names and datatypesencoding: utf8 is the default, but to avoid errors from invalid characters in CID-Title.gz, we’ll set it’s scan configuration to utf8-lossy.

post_process: a function that takes a lazyframe and returns it after applying some polars expressions.

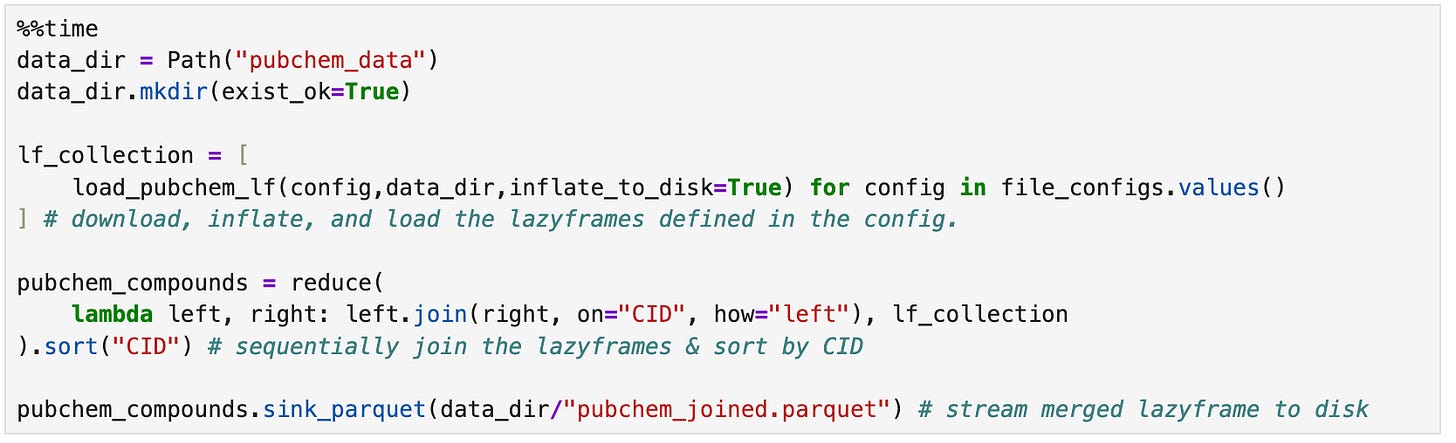

4. Load, merge, and sink the LazyFrames

Note: The following code will download ~7GB of data from PubChem the first time it runs, and then inflate the files to ~42GB, so make sure you have a decent internet connection and enough disk space before running this code. Subsequent runs (e.g. after kernel restarts) will be much faster than the first run.

If everything goes as expected, your computer will work really hard for about 10 minutes and then reward your patience with a 4GB parquet file.

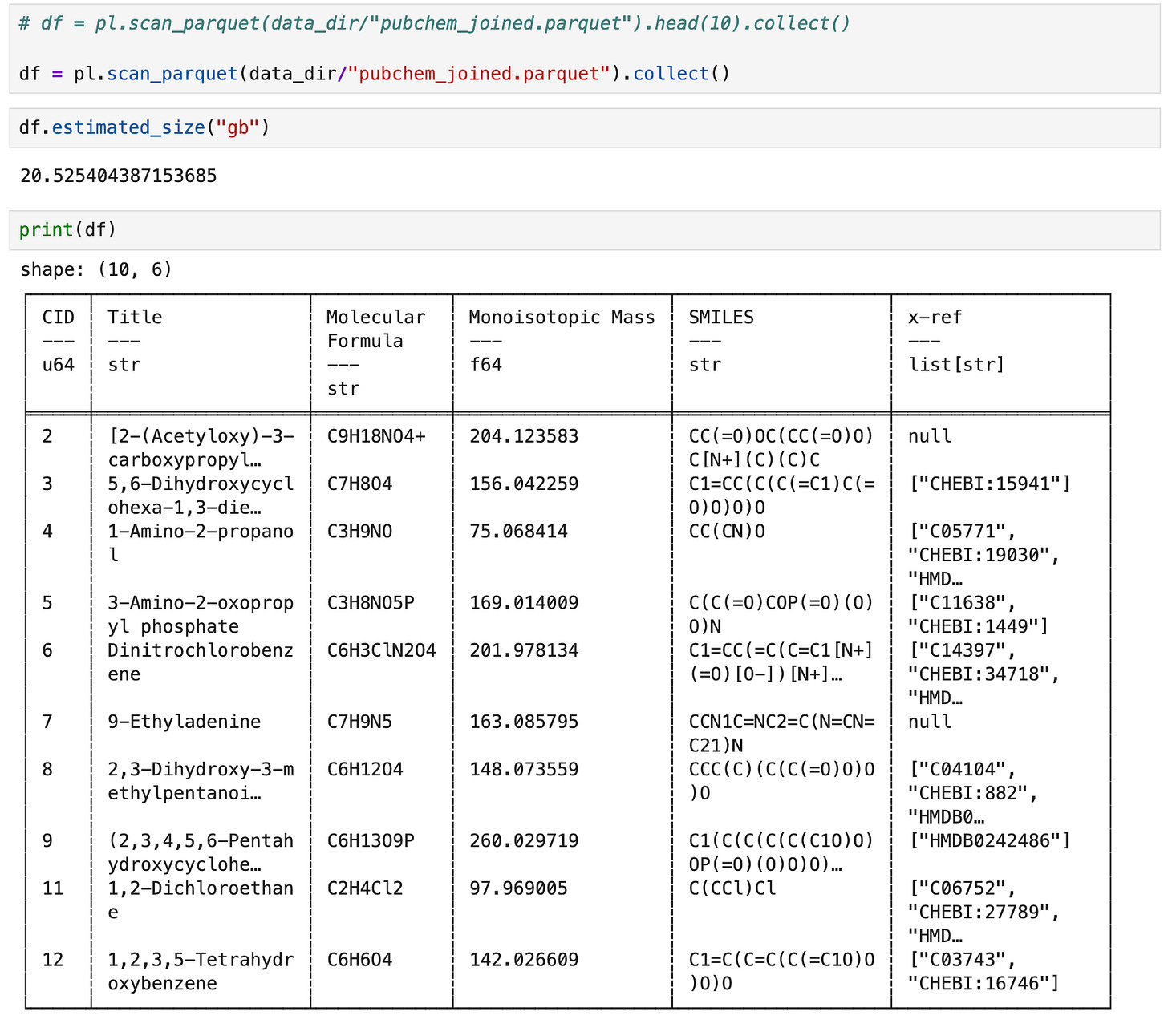

5. Inspect the parquet file

To inspect the result we can again use the streaming api, in this case the scan_parquet function combined with .head (to get the first n rows) followed by .collect (to materialize the dataframe).

If you have enough RAM to materialize a ~20.5GB dataframe, you can omit the call to head and admire it in its entirety.

Conclusion

In this post we used the polars dataframe library to aggregate chemical information for ~120 million molecules from PubChem. These data were extracted from 7GB of compressed files containing 42GB of uncompressed text. The output was a 4GB .parquet file5.

Not including the time it took to initially download the files from PubChem (but including the time it took to decompress the files), this took ~10 minutes to run on a Windows laptop with an Intel i7-1360P CPU, 32GB LPDDR5 RAM, & 1TB NVMe SSD. It took about ~5 minutes on a 2021 Macbook Pro M1 Max with 10 CPU cores, 32GB RAM, 1TB SSD6.

At the time of writing (March 2025), polars can stream data from a variety of file formats, but not directly from compressed text files - at least not as efficiently as you might expect, because it needs to inflate the entire file into memory first. This obviously negates a lot of the benefits we expect from stream processing. For now, we have to decompress them to disk before we can benefit from the streaming features, but this takes up a lot of hard drive space7.

Overall - it’s great that the combination of public data and high-quality open source software like polars enables us to do this kind of data wrangling on consumer hardware . But to wrap this up with a hot take: I think it could and should be a lot easier. Like, so easy that it’s not even worth spending a Saturday morning writing a tutorial about.

Extracting the correct table schemas from giant text files is not difficult, but it is tedious. This kind of data engineering could be trivial and wonderfully ergonomic - not to mention computationally efficient and correct - if the database bulk downloads were available in .parquet format.

Thanks for reading Bioanalytical Bees! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support our work.

Code Appendix

import polars as pl

import requests

from pathlib import Path

from functools import reduce

import shutil

import gzip

def download_file(url: str, local_path: Path) -> None:

local_path.parent.mkdir(parents=True, exist_ok=True)

response = requests.get(url, stream=True)

if response.status_code == 200:

with local_path.open("wb") as f:

for chunk in response.iter_content(1024):

f.write(chunk)

print(f"Downloaded {url} to {local_path}")

else:

raise f"Failed to download {url}. HTTP {response.status_code}"

def load_pubchem_lf(config, data_dir: Path, inflate_to_disk: bool = False):

url = config["url"]

filename = url.rsplit("/")[-1]

path = data_dir / filename

if not path.exists():

print(f"File {filename} not found in {data_dir} - downloading from {url}")

download_file(url, path)

if inflate_to_disk and filename.endswith(".gz"):

uncompressed_path = path.with_suffix('') # Remove .gz extension

if not uncompressed_path.exists():

print(f"Inflating {filename} to disk as {uncompressed_path}")

with gzip.open(path, 'rb') as f_in, open(uncompressed_path, 'wb') as f_out:

shutil.copyfileobj(f_in, f_out)

path = uncompressed_path

lf = pl.scan_csv(source=path, separator="\t", **config["scan_settings"])

if "post_process" in config:

lf = config["post_process"](lf)

return lffile_configs = {

"title": {

"url": "https://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubchem/Compound/Extras/CID-Title.gz",

"scan_settings": {

"schema": {"CID": pl.UInt64, "Title": pl.String},

"encoding": "utf8-lossy"

}

},

"formula_mass": {

"url": "https://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubchem/Compound/Extras/CID-Mass.gz",

"scan_settings": {

"schema": {

"CID": pl.UInt64,

"Molecular Formula": pl.String,

"Monoisotopic Mass": pl.Float64,

"_Exact Mass": pl.Float64},

},

"post_process": lambda lf: lf.drop("_Exact Mass")

},

"smiles": {

"url": "https://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubchem/Compound/Extras/CID-SMILES.gz",

"scan_settings": {

"schema": {"CID": pl.UInt64, "SMILES": pl.String}

}

},

"xrefs": {

"url": "https://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubchem/Substance/Extras/SID-Map.gz",

"scan_settings": {

"schema": {

"SID": pl.UInt64,

"Source name": pl.String,

"Identifier":pl.String,

"CID": pl.UInt64}

},

"post_process": lambda lf: lf.filter(

pl.col("Source name").is_in(

["Human Metabolome Database (HMDB)","KEGG","ChEBI"]

)

).group_by("CID").agg(

pl.col("Identifier").sort().alias("x-ref") # Ensure databases appear in the same order

).drop_nulls().sort("CID")

}

}%%time

data_dir = Path("pubchem_data")

data_dir.mkdir(exist_ok=True)

lf_collection = [

load_pubchem_lf(config,data_dir,inflate_to_disk=True) for config in file_configs.values()

] # download, inflate, and load the lazyframes defined in the config.

pubchem_compounds = reduce(

lambda left, right: left.join(right, on="CID", how="left"), lf_collection

).sort("CID") # sequentially join the lazyframes & sort by CID

pubchem_compounds.sink_parquet(data_dir/"pubchem_joined.parquet") # stream merged lazyframe to diskdf = pl.scan_parquet(data_dir/"joined.parquet").head(10).collect()Note that at the time of writing in March 2025, PubChem’s literature cross-references (e.g. Pubmed IDs) are not fully represented in the FTP dumps. We’ll explore ways to get more comprehensive references in a later post.

Among the three, ChEBI has the least restrictive license, which is important for commercial use. KEGG has great biological pathway definitions - widely considered to be canonical. HMDB has a wealth of spectral data and bio-material specific annotations (e.g. metabolites found in blood, stool, etc.)

Parquet is the de-facto standard file format for storing large tables in the cloud, and has many benefits compared to text-based tables like .csv and .tsv.

I like uv and highly recommend it, especially now that it’s support by dependabot. If you prefer to set up your Python environment using traditional .venv, poetry, conda, or another tool, feel free.

polars enables a lot of customization when it comes to parquet compression - we’re sticking with the defaults.

If you got this far and feel inclined, you’re more than welcome to drop a comment below with your system specs and time it took to complete. At some point - maybe after the new polars streaming engine is fully released - I may revisit this with some systematic benchmarking using resource-constrained virtual machines.

I did briefly attempt to use this plugin https://github.com/ghuls/polars_streaming_csv_decompression, but unfortunately encountered a Rust crash that I was not inclined to investigate further.