What are internal standards, and why do they matter in LC/MS?

Choosing the right standard to overcome matrix effects and improve data quality

Internal standards are a crucial tool in metabolomics. They are a simple and powerful way of addressing metabolite degradation and matrix effects, which can seriously affect the data quality. But how do they work exactly?

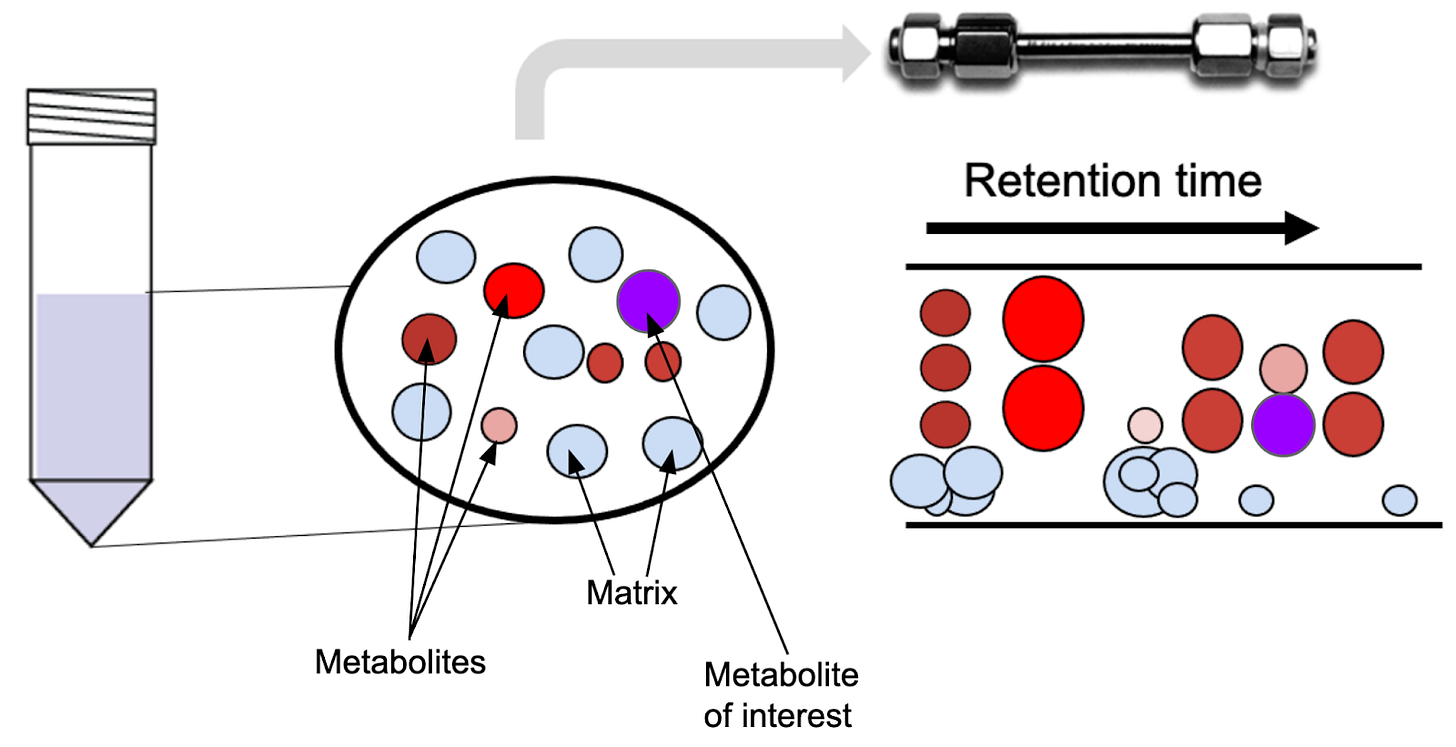

In order to understand why internal standards work, we need to dive a little deeper into how liquid chromatography works. When performing LC/MS, we analyze a complex mixture of molecules by separating them over time:

At each time point over the chromatographic separation, only the molecules that co-elute (elute together) are transferred into the mass spectrometer. The LC separation leads to essentially the generation of microenvironments within the run. Since each metabolite experiences a slightly different chemical microenvironment depending on what it co-elutes with, the signal measured in the mass spectrometer might be lower than it would without the matrix components. Internal standard helps correct for that, because it is added to the sample in known concentration (or alternatively, in the same concentration between samples - I’ll discuss how to take advantage of this below).

What are internal standards?

Internal standards are metabolites that are made of rare stable isotopes instead of the more abundant ones, in other words, they are isotopologues of naturally occurring metabolites. Stable isotopes are just regular elements with a little extra mass. The most common ones we use in mass spectrometry are ¹³C, ²H (or D for deuterium), and 15N, all slightly heavier versions of their more common counterparts 12C, 1H, and 15N. Because mass spectrometers measure mass (or mass-to-charge ratios), it can tell the endogenous metabolite apart from the internal standard based on their mass. This makes stable isotopes perfect internal standards:

They behave identically to the natural metabolite in chromatography and ionization.

The mass shift makes them distinguishable from the real analyte in the mass spectrum.

They correct for variability in extraction, ionization efficiency, and matrix effects.

Use cases for isotopologues span beyond internal standardization

Stable isotopes hold a special place in the heart of a mass spectrometrist beyond internal standardization. In addition to using isotopologues as internal standards, we use naturally occurring isotopologues to aid in compound identification. For metabolic tracer studies, we use isotopically labeled substrates that are added in the growth medium during the experiment. These diverse applications can sometimes be confusing, so it helps to remember that an internal standard is a stable isotopologue of a known metabolite, which is added to the extraction solvent for normalization purposes.

Chemically matched vs non-matched internal standards

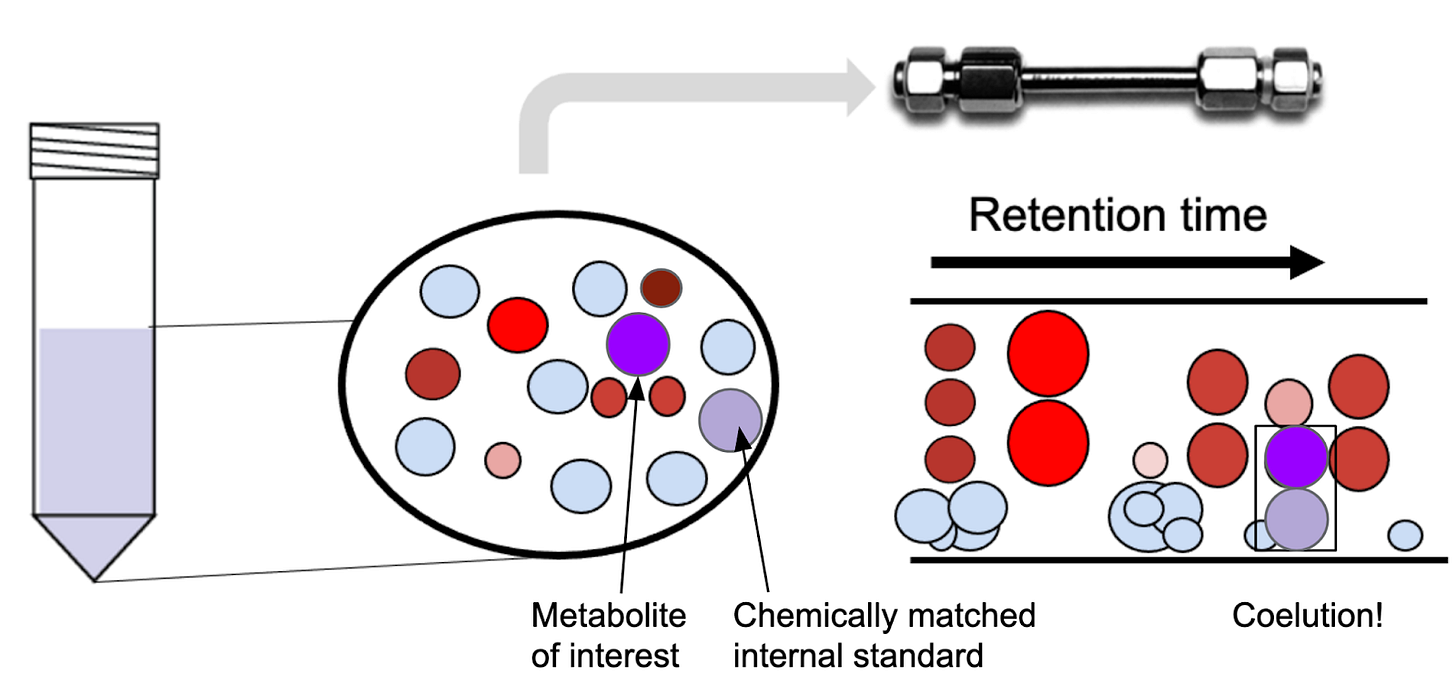

Generally speaking, an analyst can choose from two options for internal standards: chemically matched and chemically non-matched. It’s no secret bioanalysts love chemically matched internal standards; NAD for NAD, citrate for citrate, and so on. So far, we assumed that the internal standard was chemically matched to the analyte of interest (the purple and light purple circles in Figure 2). The reason for the preference for chemically matched internal standards is that the isotopically labeled standard behaves chromatographically exactly like your metabolite of interest. Any differences in microenvironments will propagate to the internal standard, as do any degradation of the metabolite.

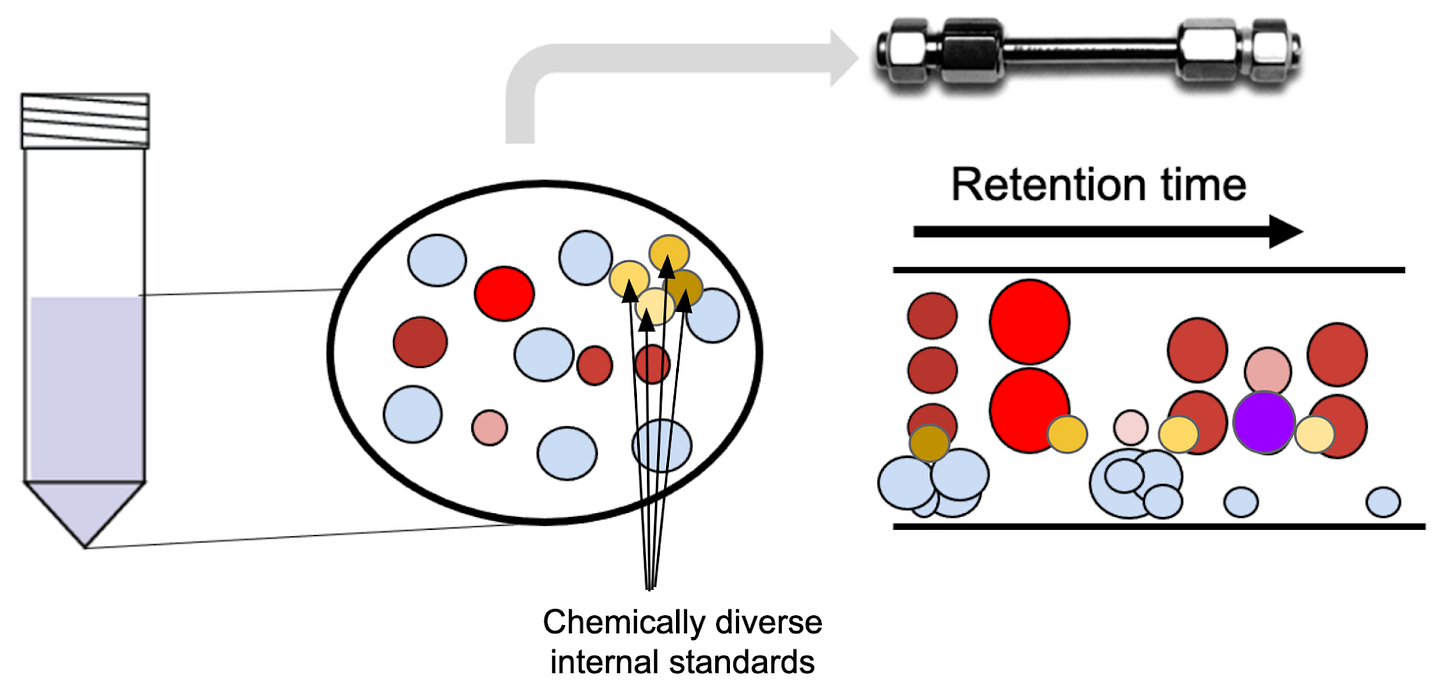

For rare metabolites or untargeted work, it’s sometimes not possible to select a chemically matched internal standard. In that case, we often use a defined mixture of isotopically labeled amino acids or a uniformly labeled cell extract. The downside is that the identity of the internal standard differs from that of the analyte—or, in the untargeted case, from most of the analytes. Adding a non-matched internal standard can still help remove variability between samples, although it won’t address the specific microenvironments or degradation. The metabolite peak area is normalized to either the internal standard that has the closest elution time, or to the average signal of the internal standards.

Practical example

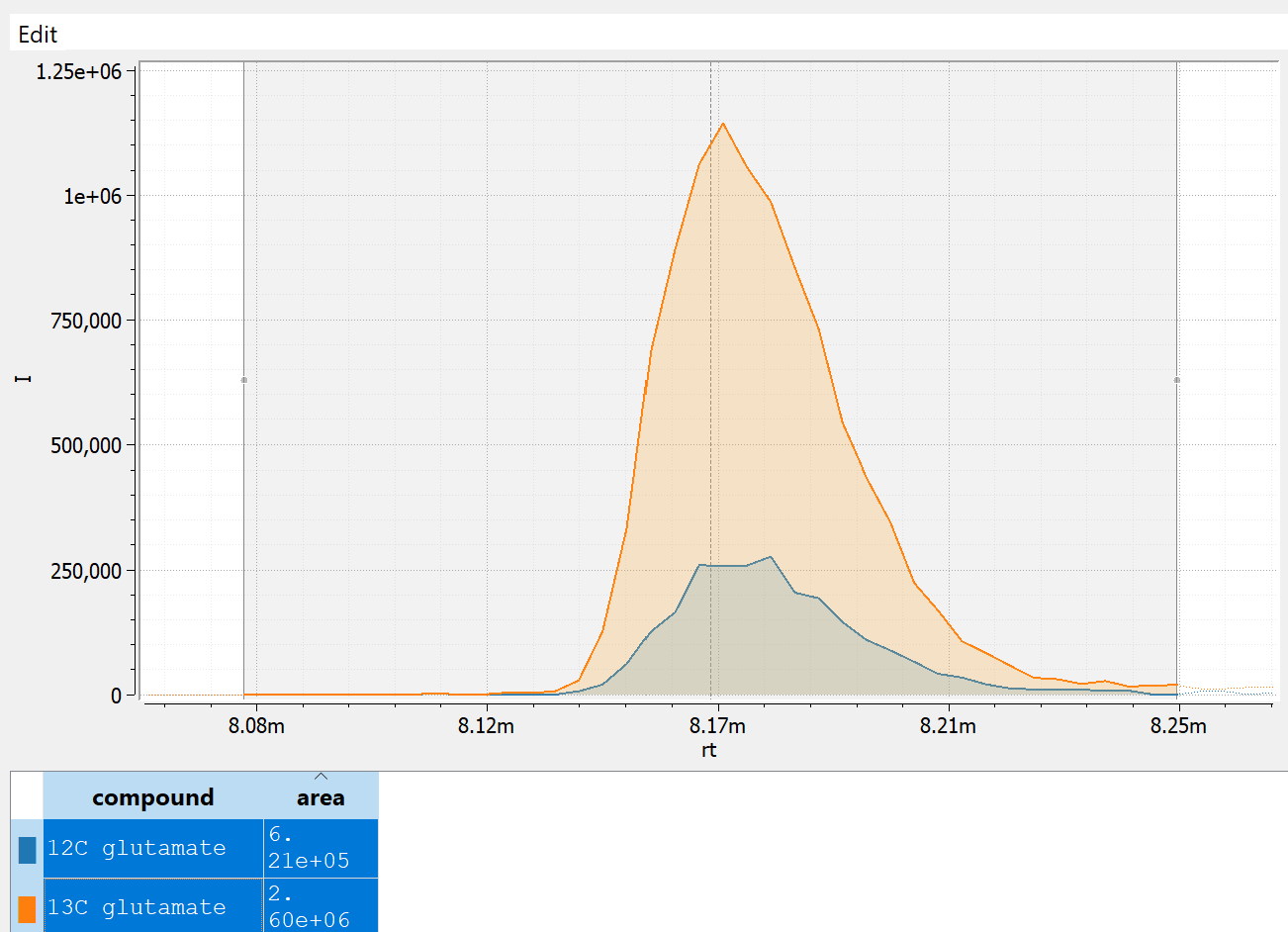

Below are some real data for a glutamate measurement visualized using emzed [1]. The trace for endogenous 12C glutamate is in blue (smaller peak in the overlay), and 13C glutamate internal standard in orange (larger peak in the overlay). The 12C glutamate has a raw peak area of 6.21e5 and while the peak area of the internal standard 2.6e6. Here, the analyst would report the abundance of glutamate as the ratio between the two:

The internal standard also allows for rough absolute quantification in this case: If we know that internal standard was present at concentration of 1 micromolar, we can infer that the concentration of glutamate in the sample would be close to a quarter of that. This estimate gets more accurate with peak ratios closer to 1.

Using labelled cell extracts instead of chemical standards

One intriguing way of overcoming the non-chemically matched standard issue for both untargeted and targeted work is to use a uniformly labelled cell extract. At its simplest, this is produced by propagating a bacterial culture growing on 13C glucose over >10 generations so that every carbon atom in every metabolite in the cells is 13C labelled. This can then be used like a chemical standard. For targeted work, the analyst can search for signal at the predicted m/z value within the retention time window. For untargeted work, the analyst can produce a library based on consistently observed 12C and 13C traces with matching retention times.

Summary

Internal standards are necessary because LC/MS introduces uncontrolled variability that affects metabolite signals. Chemically matched standards are the gold standard but aren’t always available or practical to use. When chemically matched standards are not an option, non-matched standards are better than no internal standardization, but come with compromises. Uniformly labeled cell extracts offer a way around expensive chemically matched standards, helping to correct for variability without needing a perfect chemical match. By introducing a stable isotope-labeled version of a metabolite into the sample, we get a built-in reference that accounts for shifts in retention time, signal intensity, and sample-to-sample variation.

Internal standard normalization can be applied to almost any approach from accurate quantification to untargeted profiling, making stable isotopes one of the most powerful tools in mass spectrometry.